History

The beginning of Be’chol Lashon was both intentional and serendipitous, personal and universal. Here is a brief overview of our history.

Research

For over two decades, Be’chol Lashon has been involved in research that helped emphasize the racial, ethnic and cultural diversity of the Jewish people through the ongoing publication of books, monographs, journal articles and reports.

Jewish Demographics

While today Be’chol Lashon is known for its work on racial and ethnic diversity, we were founded as a research institute, the Institute for Jewish & Community Research (IJCR). Under the direction of sociologist Gary Tobin, IJCR built on decades of experience in demographic and cultural studies to use in understanding trends in Jewish life. Tobin’s research and findings in the 1990s and 2000s serve as an ongoing source of education to help us better understand the racial, ethnic, and cultural diversity of the Jewish people.

Be’chol Lashon’s Beginnings in Research

A pathbreaker in the field, Gary Tobin’s research through ICJR shaped understanding of trends that influenced the world of philanthropy and connected to some of the most pressing issues facing the Jewish community at the time. Tobin addressed the demographic sustainability of the Jewish community and intermarriage, challenged assumptions about Jewish continuity, and helped expand understanding of the value of conversion.

Tobin expanded his work to better understand the demographic complexities of race and ethnicity within American Jewry. His pioneering study on the demographics of the racial and ethnic diversity of the American Jewish community found that approximately 20% of American Jews identify as non-white and non-Ashkenazi. It also set out the complexities of doing such studies and highlighted the ways in which traditional Jewish demographic studies overlooked and marginalized those who did not fit a narrow understanding of Jewish identity or Jewish community. Subsequent demographic studies reflect similar understanding of racial and ethnic diversity in today’s Jewish community, such as the 2021 Counting Inconsistencies study by Jews of Color Initiative and the Jewish Population surveys of New York in 2011 and San Francisco in 2019.

It was the groundbreaking findings of the IJCR study on diversity in the Jewish community in 1999 that led to the founding of Be’chol Lashon. The work of the organization since its founding has been dedicated to realizing a Jewish community that better represents this diversity.

Who Are We Talking About When We Talk About Jews?

A fundamental challenge in Jewish demographics is deciding who is being included when we talk about Jews. Depending on context the definition may rely on biology, self-identity or behavior. Biological Jews are individuals with a Jewish parent versus those Jews who practice Judaism, with or without having a Jewish mother or father. With the exception of conversion, religious Judaism sees biology as the main indicator of membership in the Jewish people.

According to Reform Judaism, as long as one parent, no matter the gender, is a descendant of Jews, then an individual is considered Jewish. Historically, and to this day, within Orthodox and Conservative Judaism, only those a Jewish mother are considered Jews. Self-identity is how individuals think of themselves. Some people think of themselves as Jews regardless of their parents‘ religion. They may have Jewish heritage or Jewish peer groups. Behavior is what people do. Behavioral Jews practice Judaism and live as Jews, with or without biological origins. This includes people who go to synagogue weekly, observe kashrut, and otherwise meet tests of behavioral Judaism. If their parents were not Jewish or they did not formally convert to Judaism, we usually exclude them in our counts.

How Many Jews Are in the World Today?

Scholars have only a rough idea about how many Jews there are in the world today. During the time of Gary Tobin’s research in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, sources reported between 13,500,000 and 15,500,000, a variance of about 15%, as defined within very limited boundaries. The real number was probably much higher. Both locating Jews and convincing them to reveal their religious identity complicates and compromises our ability to estimate the number of Jews. These factors result in undercounting Jews around the world. If we consider all the issues that plague counting the Jewish populations around the world, we are probably missing millions of Jews in our official counts.

The snapshot of the worldwide geographic distribution of Jews today is dramatically different from what it was prior to World War II. According to the U.S. Holocaust Museum, “In 1933, approximately 9.5 million Jews lived in Europe, comprising 1.7% of the total European population. This number represented more than 60 percent of the world’s Jewish population at that time, estimated at 15.3 million.” While European Jewry at the time was primarily Ashkenazi, it included a variety of Sephardi communities as well as ancient historic communities like Romaniote. There were also relatively large populations spread throughout North America, North Africa, and the Middle East. In spite of discrimination and harassment in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the world Jewish population showed a steady growth from 2.5 million in 1800 to 11 million in 1900. This growth continued from 1900 to 1938. Prior to the Holocaust that 11 million grew to 16.6 million. The majority of Jews continued to live in Europe with 9.5 million in 1938. North and South America had 5.5 million Jews. The number of Jews in Asia grew from 500,000 to one million between 1900 and 1938.

After much of European Jewry was murdered, almost one million Jews living in Muslim countries were forcibly expelled. They migrated to Israel, France, and North America, resulting in two major population centers in the United States and Israel. Today, the United States and Israel together comprise about 75% of the total world‘s Jewish population.

As they have for thousands of years, Jews keep moving from place-to-place, country-to-country. A map of the geographic distribution of world Jewry is a snapshot in time, and twenty years later that snapshot may look different again.

Why The Demographic Study Of Jews Is Difficult

Scholars, community leaders, and the public-at-large often inquire about the size, make-up, and location of the diverse Jewish population. There are methodological, definitional, ideological and political reasons why we do not have accurate counts of Jews around the world. Some of these factors apply to specific countries and some apply to overall efforts to count Jews. Some are unique to Jewish demography, and some are more universal issues affecting any census, specifically, or counting racial, ethnic, or religious groups. The demographic study of Jews is difficult for a variety of reasons.

Some countries do not survey religion

Some countries, like the United States, do not ask about religion in their census counts of the population. A number of interest groups (especially many Jewish organizations) are concerned about the separation of church and state, and do not want the government inquiring about religion. Therefore, we rely on a variety of surveys to try to estimate the Jewish population, including the number of diverse Jews. Many are unreliable.

Some Jewish communities are highly dispersed

Even in communities with significant Jewish populations, people are more likely to be scattered among the general population than in previous generations. Jews in the United States also live in the suburban fringes of many metropolitan areas, far from any Jewish population center, making them difficult to locate. Finding Jews to respond to surveys outside major metropolitan areas is an even more needle-in-a-haystack endeavor.

Some Jews do not want to be found

Some Jews may hide their identity or background from survey takers or a government census. The Institute for Jewish & Community Research conducted methodological tests that confirm that there are many Jews that refuse to reveal their identity. Gary Tobin took known lists of Jews and asked them about their religion and found that many denied that they were Jewish. Some groups of Jews are more reluctant than others to reveal their religious identity. This includes those who tend to mistrust governments; those who have been victims of persecution; those who reject their religious identity; and those who think of themselves as ethnic Jews rather than religious Jews.

Many people do not know their Jewish heritage

Finding Jews in the United States is a simple task when compared to finding individuals and groups with Jewish ancestry in some countries around the world. This is largely in part due to the overall acceptance of Jews in American society and the safety this offered to be openly Jewish. The sophisticated methods of survey research do not apply, and written records sometimes do not exist in some communities. Oral traditions or ritual practice are the indicators of Jewish roots and help find some people. Others do not know about their religious origins, especially those descended from ancient, but now assimilated Jewish communities. For example, many descendents of Spanish and Portuguese Jews have no idea about their Jewish ancestry.

Researchers do not look for some Jews

Some of the problems in surveying Jewish demographics result from where researchers have thought to look. Some of these issues cause minor shifts in the total numbers, and others can cause huge differences. Some communities, such as the Lemba of South Africa and the Ibo of Nigeria are omitted entirely. For example, when studies count Jews in South Africa, they traditionally count Jewish descendants from Europeans who settled there. Researchers do not look for and count the Lemba, an indigenous people who have practiced Judaism for centuries. Nor do researchers look in Uganda for black African Jews where the Abayudaya practice Judaism. Many of the official counts in most of sub- Saharan Africa, are of non-indigenous populations only, a strong statement about who is a Jew and who is not.

The Demographic Study Of Jews From Racially, Ethnically, And Culturally Diverse Backgrounds In The United States.

Americans are increasingly characterized by choosing their own paths religiously and in their relationships, whether this is changing religions or choosing partners with racial, ethnic, or cultural backgrounds different than their own. The American Jewish community, which includes Jews of racially, ethnically, and culturally diverse backgrounds, is part of these national phenomena.

Based on Gary Tobin’s research, we estimate at least 20% of the Jewish population is racially and ethnically diverse, and includes African, African American, Latino (Hispanic), Asian, Native American, Sephardic, Mizrahi and mixed-race Jews by birth, heritage, adoption, and marriage. Gary Tobin set out to try and gain insight into the demographics of Jews of Color. Understanding this number is challenging and requires examining a number of different sources.

First, according to the 2002 Institute for Jewish & Community Research study and the 2000 NJPS study, a little over 7% of America’s 6 million Jews say that they are African American, Asian, Latino/Hispanic, or Native American or mixed-race, for a total of about 435,000 individuals. This includes 85,000 who say that they are some race other than white but do not classify themselves more specifically. Second, the NJPS 2000 found 120,000 Jewish adults living in the United States who were born in Latin America, the Middle East, Asia, and the Caribbean (not including Israel). We estimate that over half of this foreign-born population (not including children) is comprised of diverse Jews, adding another 65,000.

Third, the number of Israelis living in the United States is under great dispute, including those of racially diverse backgrounds. For example, the 2000 NJPS found only 70,000-93,000 Israelis living in the United States, while the 2002 New York demographic study showed about 50,000 Israelis in New York alone. The 2000 U.S. Census reports almost 200,000 people who speak Hebrew at home. A 2003 study by the Israeli Foreign Ministry showed almost a half million (500,000) Israelis living in the U.S.

Therefore, based on the 2000 U.S. Census, we are conservatively estimating the total number of Israelis in the United States at 200,000. Because approximately half of the population in Israel is of Mizrahi, Sephardic, and African heritage (before the migration from the former Soviet Union), it stands to reason that about 50% of Israelis in the United States could be Mizrahi, Sephardic, or African Jews (who are not included in the other categories listed). Therefore, we conservatively estimate that 100,000 Israelis living in the United States are of diverse backgrounds, or 1.7% of American Jews. This brings the total to 600,000 diverse Jews, or about 10% of the population.

Fourth, a question regarding Sephardic heritage was not asked in the 2000 NJPS, although the 1990 National Jewish Population Study showed that 8% of American Jews said they were Sephardic. Is the real percentage 10%? More? We do not know, other than to surmise it is considerably higher than is reported.

The number of Jews with some Sephardic heritage is likely to be grossly underestimated in many Jewish surveys, including the NJPS. Sephardic heritage is especially apt to be lost in individuals’ self-reporting. Many people do not know about their Sephardic background, especially given the propensity of different groups of Jews to intermarry over generations throughout the Diaspora. Taking into consideration all these factors, we are conservatively estimating 10% of the United States population has some Sephardic heritage, in addition to those who say their race is Latino/Hispanic. We have taken into account potential overlap in this reporting and adjusted our estimate accordingly.

Adding 600,000 Sephardic Jews or 10% of the Jewish population together with 600,000 or 10% of Black, Asian, Latino and mixed-race Jews means 1.2 million or 20% of the Jewish population in the United States is diverse. This includes individuals who have converted to Judaism, individuals who have been adopted into Jewish families and raised as Jews, the multiracial children of partnerships between white Ashkenazi Jews and people of color, and those who are themselves the generational descendants of Jews of color and those of Sephardic and Mizrahi heritage.

The Lost Tribes of Israel

Some Jewish communities around the world have ancient Jewish heritage and consider themselves descendants of the “Lost Tribes” of Israel. Around 926 B.C.E., the kingdom of Israel split in two. Previously, all twelve tribes of Israel had been united under the monarchies of Saul, David, and Solomon. But when Solomon’s son Rehoboam ascended to the throne, the ten northern tribes rebelled and seceded from the union. This left only two tribes—Judah and Benjamin—under the control of the king in Jerusalem. From that time on, the tribes were divided into two nations, which came to be called the House of Israel (the ten northern tribes) and the House of Judah (the two southern tribes).

When the Assyrians conquered the House of Israel around 722 B.C.E., they deported the native populations to other places throughout the Assyrian kingdom. Many Israelites made their way across the Silk Road ending up in Asia and Africa, where they intermarried with the peoples among whom they settled. They eventually abandoned their distinct identity, and their culture was lost to history. These are the groups who are referred to as the “Lost Tribes” of Israel.

More rigorous scholarship about Jewish migration in Africa and Asia is needed, and such studies are being designed by the Center for Afro-Jewish Studies at Temple University:

There are quite a number of peoples today who cling to the ancient tradition that they are descended from the Jewish Lost Tribes: the tribesmen of Afghanistan, the Mohammedan Berbers of West Africa, and the six million Christian Igbo people of Nigeria. Unquestionably, they all practice certain ancient Hebraic customs and beliefs, which lends some credibility to their fantastic-sounding claims.

According to conversion advocate Lawrence Epstein, Rabbi Avichail distinguishes between the conversions that occur for members of the Lost Tribes and the conversions of gentiles:

Normally, potential converts are turned away and told to return after a period of time so that the prospective Jew can offer convincing evidence of sincerity. For Marranos [pejorative term for Anusim] and remnants of the Lost Tribes, who presumably have remnants of a Jewish soul, however, Rabbi Avichail believes no such discouragement is called for. In fact, for the rabbi, the formal act of conversion is simply “to bring back people with a Jewish past,” and is not a typical conversion.

Why We Prioritize Diversity As A Jewish Value

Jewish Diversity in the United States

Diversity has been an indelible characteristic of the American Jewish community for its entire existence. Today we can understand this diversity as a result of historical antecedents as well as contemporary social forces at work. The Jewish community today is growing and changing through intermarriage, conversion, and adoption. Some of the individuals entering the community via these avenues are people of color.

As Jews continue to be integrated into the overall American society, it should hardly come as a surprise that growing numbers of Black, Asian, Latino, Indigenous, and mixed-race individuals are part of the Jewish community. This growth augments a racially and ethnically diverse Jewish population that has existed in America for hundreds of years. The first American Jews were Sephardic and African, before Ashkenazi Jews came to the New World.

Ironically, Jews, as a group, were defined as non-white by the American majority well into the 1950s and early 1960s. It is no coincidence that racially-restrictive covenants and housing laws in America, prior to the late 1940s, targeted African Americans, Asians, and Jews, all considered to be foreign, non-white racial groups.

On the timeline of Jewish existence, the white status of Jews is something of a novelty. For some Jews, it is difficult to absorb that all Jews were recently considered to be non-white. Still other Jews, oddly enough, will never think of themselves as white at all. Some Jews still consider themselves to be part of a minority that exists outside the white mainstream of America. They feel that they are strangers in the land, still. Yet, as they relate to people of color, most Jews in the United States benefit from and identify with whiteness, even if they can sometimes empathize or identify with people of color.

What accounts for this racial diversity?

Around the world, including within the United States, there are long-established families and communities of color who have been Jewish for generations. Additionally, some number of intermarriages between a Jew and a non-Jewish partner are also interracial relationships. Even when the non-Jewish partner does not convert, their children may grow up with a Jewish identity, with multiple religious identities, or with no religious identity at all. Some people of color become Jews through formal conversion, and still others live as Jews transforming their identity psychologically and functionally without undertaking rites of conversion. An increasing number of children of color become Jewish when they are adopted by Jewish parents. Many, but not all, of these adopted children undergo a formal conversion while they are still minors and grow up just like other Jewish kids in America.

Race in America

The definitions of racial categories are changing for sociologists, anthropologists, and demographers, as well as the public. Conventional categories are muddled and often were artificial and problematic from their inception. We have outgrown the definitions we created. Moreover, language does not exist to talk about the complex combinations of race, religion, ethnicity and nationality that may exist within one individual. Diversity in American Jewish families mirrors that of the diversity that exists in the broader American society.

Like many Americans with multiple heritages, Jews of diverse backgrounds have multiple identities that are sometimes conflicting, complicated and difficult to resolve. Others embrace and are comfortable with their multiple identities. Diverse Jews who do not feel welcomed by the Jewish community may find it less complicated to identify with his or her racial community than to identify as a Jew. At the same time, they may face discrimination from their racial group for their identification with Judaism. Jews of color may have bifurcated identities; culturally relating to their respective racial communities and religiously to Judaism. Others navigate multiple identities with ease, and feel privileged to be part of so many different cultures.

The Importance Of Jewish Diversity

Racial and ethnic diversity in the Jewish community is important for many reasons. Here are five:

-

Racial and ethnic diversity are the hallmark and soul of the Jewish experience.

-

The percentage of diverse Jews within the American Jewish population is increasing through returns to Judaism, conversion, adoption and interfaith unions.

-

Diverse Jews deeply identify as Jews and have a strong desire to build community.

-

Diversity within the Jewish community helps create connections with other racial and ethnic groups and fight anti-Semitism.

-

Diversity helps make Judaism more meaningful.

Diversity has always been a vital part of Jewish history and heritage. Throughout Jewish history, the Jewish people have borrowed from and added to other cultures wherever they lived, in Egypt or Ethiopia, in Cartagena or Calcutta, Russia or Romania. Jews have always grown by the addition of people from the surrounding cultures– changing,adapting and becoming richer with each addition, whether by choice or by force. No single ethnic or racial group holds the “true Jew” card. Jews have survived by being an adaptable people.

Internal And External Challenges Of Jewish Diversity

The Jewish community is troubled by a number of challenges: denominational differences, attempts to define who is a Jew, questions around legitimate expressions of Judaism, definitions of participation and belonging, among others. Under which auspices someone converts, how they study, and how they live their Jewish lives are all controversial. Jews of color are often caught in the maelstrom of the Jewish community’s inability to resolve issues of standards, dissension, and mutual suspicions. A healthy Jewish community requires effective measures to deal with this internal strife.

The Jewish community is often too quick to reject Jews who are on these paths and journeys, looking to who is “in” and “out,” rather than where individuals are on a continuum. Like many others in all religious groups across the American spectrum, many Jews of color are on their own spiritual and religious paths, sometimes resulting in conversion after living as a Jew for many years. Some may bring with them religious practices from their former religion until identity transformation to being Jewish is complete. Furthermore, conventional wisdom about race and religion do not necessarily apply (i.e., “Asians are Buddhist” or “Blacks are Christian”). The images of Jews are similarly inaccurate.

Of course, these tensions are not new. Jews have always faced contentious intra-communal issues, plagued by familial and tribal conflict from the beginning. Over time, differences became entrenched through ritual practice, loyalty to various religious leaders, nationality, origin, and a host of other issues. Internal strife, however, was almost always attenuated by external threats, oppression, and persecution. Jews were forced into geographic and communal proximity by the majority populations around them or forced to hide their identity, as the Anusim have been for centuries.

Jews have primarily used three techniques to cope with internal strife and external oppression. The first is to become inward looking and self-protective. Strangers are kept at bay and newcomers are rejected. Jews carry the ghetto with them either physically, psychologically, or both. The ghetto strategy, whether imposed externally or internally, creates an illusion of unity: But is a closed system that becomes rife with internal divisions. The second is to abandon Jewish identity completely, to assimilate and ultimately disappear into the majority population. Some Jews assimilate to the point of abandoning their distinctive Jewish identity and behavior. The disappearing strategy provides more options and choices-but without Judaism. The third was perfected by the Anusim–living inwardly as Jews and outwardly as gentiles. For generations, the descendants of those who were forced to convert to Christianity, known as “conversos” (converts), “marranos” (swine), “crypto-Jews,” and now “b’nei anusim” (children of those who were forced), passed their secret to their children and grandchildren. This legacy of fear and hiding remains so strong that even today many b’nei anusim do not risk revealing themselves. The goal in modern societies is to have both identity and integration, among the greatest challenges of the 21st century.

All of these issues are pressed even harder upon ethnically and racially diverse Jews. In the same way that Jews of color are a microcosm of the ways that Jewish organizations and institutions alienate many Jews, so is this population a microcosm for the “who is a Jew” issue. The constant questioning of the legitimacy of others now characterizes much of the rhetoric and behavior of the Jewish community. Has someone converted properly? When a child is adopted, are all the rituals followed? What is the nature of someone‘s lineage? Is the mother “really” Jewish? Halakah is important and so are standards. But the Jewish community has different and evolving standards. Are they applied uniformly and fairly?

Be’chol Lashon envisions a future where the history, holidays, stories, and experiences of Jewish people from racially, culturally, and ethnically diverse backgrounds from around the globe are celebrated by all Jews as an integral part of what it means to be Jewish.

Studies

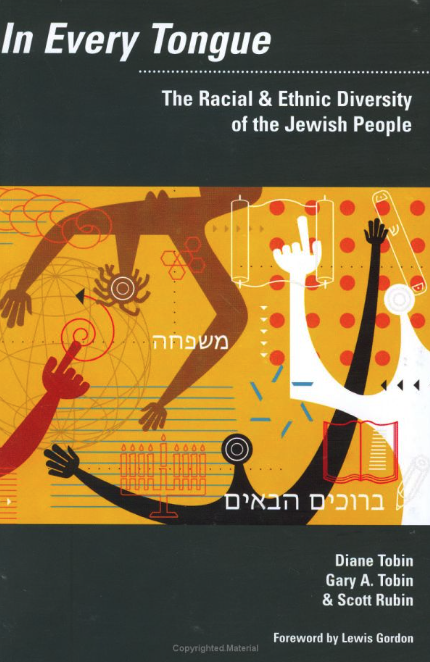

The research conducted by Gary Tobin and the Institute for Jewish & Community research led to the publication of several important books, monographs, journal articles and reports.

"In Every Tongue needs to be studied, wrestled with, built upon, and integrated in the public policy thinking of the organized Jewish community. The future of the Jewish people depends on it." — Rabbi Irwin Kula, CLAL, New York

"This is a terrific article. Solid background as to the importance of the issue, good introduction to important concepts, and suggestions for implementation." — Reviewer

"Gary Tobin has written the most important and challenging book in American Jewish public policy in years. People may agree or disagree, but no one interested in contemporary Jewish life will be able to ignore this work." — Steven L. Spiegel, UCLA professor of political science

"With empathic intelligence, the authors examine the ambiguities and ambivalences that confront the rabbi who is torn by seemingly conflictive loyalties." — Rabbi Harold M. Schulweis, rabbi, Valley Beth Shalom

"As this important book makes clear, it is high time for all of us to insist that colleges promote a civil yet robust exchange of ideas—the very foundation of a liberal education." — Anne Neal, president, American Council of Trustees and Alumni

"I quote the Study of Jewish Culture in the Bay Area all the time, as it is more apropos than ever." — Lenore Naxon, Naxon Consulting

Note: The Ashkenazi nusach (style) traces its roots to the Jewish communities of Central Europe.

Note: The Sephardic or Spanish-Portuguese nusach (style) originated in Spain and Portugal.